Mesopotamian Sculpture – Meaning, History and Representatives

Contents

What is Mesopotamian Sculpture?

The Mesopotamian Sculpture (the State of Iraq at this time), was located in the valleys through which the Tigris and Euphrates rivers flow, so there, several important civilizations settled in antiquity. They were the Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians and Assyrians. These civilizations were made up of two different races, the Semitic Akkadians of the East (later called Assyrians and Babylonians) and the Sumerians.

From Mesopotamia, travelers from Sumer, Babylon or Assyria remembered the shapeless mounds where cities and towns had once stood. Yet the ancestral art of this part of the world ranks alongside the cultural achievements of any of the ancient civilizations. It was here, for example, that writing was invented, it was also here that the first wheel is believed to have been made, and also where the first cities appeared some years before the pyramids of Egypt. Likewise, it was here that the potter’s wheel was invented and where some of the finest ancient ceramics outside of China were produced.

Excavations to find remains of this civilization were carried out by the Frenchman Botta in 1842 on a mound near the Tigris in northern Mesopotamia. They found on the covered walls a strange sculpture that was quite different from anything anyone had ever seen before. The mound covered the remains of a large palace that had been built in the 8th century BC by an Assyrian king named Sargon II. Simultaneously, some reliefs were found that testified to the grandeur of Mesopotamian art.

The reliefs showed men in strange clothing building a palace or city and others rowing boats across a sea in which huge fish, crabs and other sea creatures, including a Triton, were floating. From adorning the palace of an Assyrian king, built more than 2,600 years ago, these carved stone slabs were taken to France, to the Louvre Palace, Paris of the kings of France. Now one of the best art museums in the world.

Definition of Mesopotamian Sculpture

In ancient Mesopotamia, palaces, temples, cities, and great libraries of clay tablets covered with the curious writing called “cuneiform script” were gradually discovered. Just as scholars had learned to read the hieroglyphic writing of Egypt, so in time others had learned to read the cuneiform writing of ancient Babylon and Assyria in order to understand the languages that had been spoken in different parts of the country at different times. The history of Mesopotamia was more turbulent than that of Egypt, and involved more races of people.

The reliefs found by the Frenchman Botta, were the first types of art from this part of the world to be seen from this huge 2,000 year old civilization and they were Assyrian. Thus, the Assyrian empire flourished approximately 1200-600 B.C. After Botta’s discovery, earlier works gradually came to light so that, by degrees, scholars were learning much not only about the Assyrians but about the Babylonians, who dominated the empire, about 1800-1200 BC and the Sumerians even earlier, who settled in this land between the two rivers about 4000 BC. To their amazement they found that the Sumerians, whose name had been forgotten, were not savages or uncivilized, but a highly developed people who had built temples and cities, dug canals, developed cuneiform writing and produced numerous exceptional examples of megalithic art, as well as sculpture and goldsmithing.

How did Mesopotamian sculpture develop?

The earliest Sumerian works found were from the Sumerian city called Ur and in a place a few miles from it, a temple of a goddess named Nin-Kharsag was built around 3100 BC. So, archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley discovered the tombs of kings and queens that probably date back to about 3500 BC. The religious beliefs of the Sumerians, Babylonians and later Assyrians were very different from those of the Egyptians. The dead were always placed with all the things their relatives thought they would need (including the bodies of their servants and courtiers if they were kings and queens), but no statue of the dead man or woman was placed in the tomb, no evidence of how they had been in life, in carvings or painted on the walls, and no statue of a god or goddess accompanied them. However, in the tombs there are exquisite examples of funerary and religious art, including small figures made of metal, or carved in wood and covered with silver, gold, shells and other materials. There are also relief carvings of the fronts of some harps, the heads of bulls, cows or deer made of gold, silver or projected copper. Sometimes the eyes, beards and horn tips were made of a beautiful blue stone called lapis lazuli. A chariot or sleigh was decorated with the protruding heads in gold and silver of lions, lionesses and bulls.

Likewise, two strange figures were found, representing a situation of a ram on its hind legs and its front tied by silver chains to the branches of a bush. Also found were the figures of rams that had been carved in wood first and then covered with thin sheets of gold and silver with scales of white shell and lapis lazuli to represent tufts of hair. These sculptures are in the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania Museum.

When the ancient temple of Kharsag Nin was excavated, the remains of four standing statues of bulls were discovered. They are the oldest type of copper statues found anywhere so far. Two of the bulls were removed and restored, which are now in the British Museum and in Philadelphia.

At the bases and corners of their temples, the Sumerians and Babylonians placed small brick boxes, each constructed of copper figures. They represented the king who founded the temple but shown as a laborer and carrying a basket of mortar on his head. From the waist down the figure tapers to a point, where the name of the king and the temple was engraved in cuneiform script on the figure or on a brick in front of it. So, these foundation figures were very valuable to tell their discoverers the structure of the building and when it was built. In some buildings a row of small three-sided brick boxes were placed along each wall, just below the floor and in each box a rough modeled and colored figure representing a human being, an animal, a snake or an animal half fantastic creature and half human. They were guardians, to ward off bad luck, and before each one an offering of some grains or meat was placed.

Larger statues were also made from very early times, depicting kings or gods, very few of which are in perfect condition. A very early marble sculpture was discovered from an ancient Sumerian city called Nippur. An inscription in engraved cuneiform script depicts a king named Esar who lived somewhere around 3000 BC. This statue was small and features a man standing with his feet together and his hands folded in front of his chest in the attitude that, in this part of the world, still expresses reverence. The lips are smiling, but the eyes are hollow voids. Probably the sculptors inserted some colored material to form the eyes, like the sculptors of Egypt. Over the eyes they made grooves in which there were strips of metal to represent the eyebrows. One of the most interesting things about the Esar King is the way he dressed. He wears a kind of skirt from waist to ankles that seems to be made up of rows of petals. Apparently it was the sculptor’s way of depicting a sheepskin garment with untrimmed wool hanging in loose tufts.

Mesopotamian Sculpture Types

Reliefs

Relief sculptures date from early Mesopotamian times, also depicting men wearing skirts of the type described above. Reliefs are stone slabs or vertical stone slabs, and stelae, which were set up in cities or temples to commemorate some event, such as a victory or the building of a temple. Fragments of many Sumerian stelae have been found. Sometimes they were located far from Sumer in the ruins of a city to which they were brought in triumph, as part of the spoils of a conquered Sumerian city.

Some of the best stelae came to light at Susa, the capital of the country called Elam, in mountainous land east of Sumer. These date from around 2400 B.C., when Naram Sin, the king of a Sumerian city-state called Lagash, conquered Elam and laid siege to Susa. These stelae were carved monuments, showing soldiers marching through the mountains and showing the king himself running over a conquered enemy. Likewise, it is evident from the reliefs, how hundreds of years later, they stormed the town of Susa, in turn Lagash, and led the empire to the defeat of their ancestors. Thus, the ruins of the forgotten city were found 3 thousand years later and brought to Europe, to the Louvre Museum in Paris, France.

In this regard, the Sumerian sculptures that caused the most interest and excitement in Europe were unearthed from the Lagash mound. There were a large number of these statues, and the inscriptions on them showed that they represented some of the governors, kings and priests of Lagash, especially one whose name was Gudea, who lived about 2400 BC. So, more than 20 of these Lagash statues are in the Louvre Museum, and at least six of them bear the name of Gudea. Others are in London and America. Therefore, the reason why these statues caused such interest was that, besides being important because of their antiquity, they were works of stone sculpture carried out with their own techniques, better than those produced in Egypt and other countries, to such an extent, that artists and sculptors as well as archaeologists were impressed by them. Thus, when they were discovered, in 1901, some European sculptors began to feel that the plastic art of their own time was not as worthy, magnificent, simple and serene as such work, which was often fussy and sentimental, represented in a trivial way, with temporary things. The Lagash statues impressed them because they had the qualities they felt the sculpture of their time lacked.

The statues were carved with marvelous skill from one of the most difficult of all stones to carve, Diorite. Working in such a difficult material the sculptors were able to represent everything in the simplest possible way. Removing all unnecessary details and keeping the figure compact, without projections. The sculptor concentrated on making his piece of stone a well-balanced form, not worrying about getting the proportions of the human form right, probably, he tried to make the face like any particular person.

It is said that the statues were found buried in a mass of ashes, charcoal and fire-reddened bricks. The triumphant enemies who finally defeated and sacked Lagash set fire to them, but not before they had removed the heads of the statues of their kings and governors and thrown them from their pedestals. Each statue was decapitated when they were discovered more than 4,000 years later. Thus in one of the Gudeas, sitting in the Louvre Museum, an expert examining it noticed that the neck fracture had the same shape as a head that had been sent to the Louvre from Mesopotamia about ten years earlier. The head was brought back and matched exactly. Only two or three of the statues found at Lagash have been reunited with their heads. One of them is in the British Museum.

Assyrian and Babylonian Sculpture

The Babylonians and later the Assyrians, whose empires followed those of the Sumerians in Mesopotamia, carved some statues in the round, partly perhaps because they had to bring stone from great distances, and was the reason why stone is used very sparingly. Only one stone statue of an Assyrian king has survived intact. It represents King Ashurnasirpal, and is in the British Museum. He ruled Assyria from 885-860 BC and the statue was found in the ruins of his palace by an Englishman named Layard. This statue was perfectly carved in great detail with the king tightly wrapped in a long fringed robe. Ashur stands rigidly upright, his bare feet together, his eyes open under strong eyebrows looking forward, his nose straight and large, beard and hair stiffly curled and cut.

Moreover, a wonderful Babylonian relief in terracotta sculpture, known as the Burney Relief (1800-1750 B.C., (British Museum), was also found. Originally from southern Iraq, this Isin-Larsa or ancient Babylonian high relief plaque shows a nude winged goddess, with bird-like talons, accompanied by owls and perched on lions. Other fascinating Babylonian works include the terracotta sculpture known as the Queen of the Night (1775, British Museum), and a wonderful example of mosaic art known as the Banner of Ur (c.2500, BM, London). Made of shell, limestone, lapis lazuli and bitumen, it was discovered in the royal cemetery at Ur.

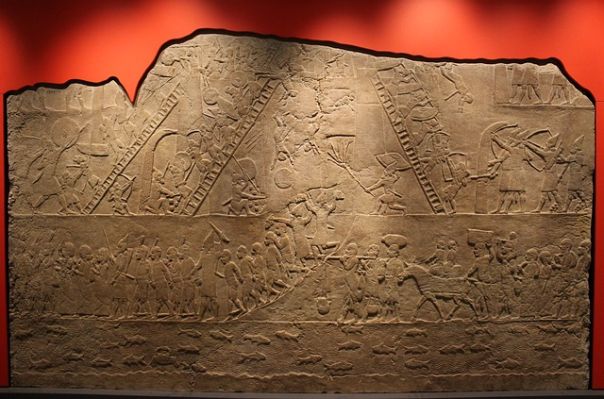

Assyrian Sculpture was almost all in the form of bas-relief (bas-relief) and served as decorative art to adorn buildings. The walls of all rooms were lined with stone slabs as found by Botta, on which the carved reliefs were illustrations of the king’s power and the success of his campaigns. Thus, Kings and gods are shown taking part in religious ceremonies, Assyrians fighting to conquer their enemies, besieging cities, making ships, transporting men and chariots across rivers, parading or executing prisoners, carrying away booty or statues of the gods of the defeated countries, riding horses and camels in the hunt for wild animals. An interesting and surprising fact to learn from the reliefs is that the Assyrian soldiers sometimes crossed rivers resting on inflated skins.

Another momentous fact is that Assyrian reliefs almost never show quiet domestic scenes. The Assyrians were fierce warriors who were hated and feared by their neighbors, and their fierceness and cruelty is reflected in their art.

Women rarely appear in Assyrian sculptures, much less children. Men are shown wearing garments that hide most of the body, and are made of heavy fabrics decorated with bangs and tassels. But the muscles of the bare arms (and legs when visible) are made very prominent. They are not generally the right shape or in the right position, apparently the anatomy is not accurate, but nevertheless they give a tremendous impression of strength and power.

The same strong, cruel face, with stiff curly hair and beard, appears again and again in the reliefs, whether the carving represents a king, a god or a priest, although servants and lesser men are often shown without the beard. Humans are shown in profile, that is, from the side, but the eye, like the eye in Egyptian sculpture, is carved as seen from the front. In Assyrian reliefs the shoulders are not twisted but rather face the viewer, nor is the main figure shown much larger than the others, though sometimes it may be a little taller.

The Gods or guardian spirits sometimes have the heads of birds or animals, and carry in one hand a basket or bag with a handle and in the other an object rather resembling a fir cone. Sometimes they are shown taking part in a date palm fertilization ceremony.

The Assyrians were also known for their ivory carvings and gold work, mostly in the form of personal objects, accessories and rare instances of chryselephantine sculpture of valuables.

Assyrian Animal Sculptures

There is not the same uniformity in Assyrian animal sculptures as with human figures in Assyrian reliefs. Few artists anywhere have ever been able to equal the Assyrians in the wonderful and natural way in which they have depicted horses, lions, bulls and other beasts in their hunting scenes, and some of the best of these wonderful sculptures are in the British Museum in London. There is also a large collection of reliefs from the ruined palaces of three Assyrian kings, which were excavated during the years twelve to fifteen after Botta’s first discovery. In them, a king can be seen killing lions from the back of his chariot, with his bow and arrow or with his spear. Men furiously riding horses and shooting as they ride. Wounded lions and lionesses savagely attacking the running horses and more seriously wounded ones, who are crawling on the ground, evidently howling in agony. Some of the scenes are very painful and cruel, but they are extraordinarily vivid and true. Thus the viewer feels assured that the sculptors had actually seen what they illustrate, knew and understood the animals and were passionately interested in them and how they moved.

Sculptures of Strange and Fantastic Figures

In addition to natural carvings of animals in relief, Assyrian sculptors, like those of Egypt, carved strange fantastic creatures that were half human and half animal. They also invented the curious method of carving that was partly round and partly relief. On both sides of large gates and doors colossal statues of kings’ palaces, which were of lions or bulls, placed usually winged and sometimes with the heads of men. They were carved in a block of stone, fourteen feet or higher, in such a way that anyone who can approach from the front sees the animal, for they were carved in the round with their forelegs to the side. But approaching from the side, one sees the animal in relief, apparently walking, for the sculptor had placed an extra, that is, a fifth leg. Sometimes an assistant is shown in distress beside the animal.

Mesopotamian Sculpture Legacy

Cuneiform writing was the first written language. It was invented by the Sumerians in about 5,000 BC. The Cuneiform language was written on clay and reliefs. Even after the fall of the Sumerians, other civilizations used cuneiform writing as their way of writing.

The Invention of the Wheel

The wheel was arguably a form of sculpture created in ancient Mesopotamia. The first wheels were invented around 3,500 BC. These early forms of wheels were placed under heavy objects to roll them along rollers. After that, people discovered that placing rollers under heavy objects made them even more easily movable. These runners and rollers developed into the eventual wheel that is used today.

Irrigation Canals

Irrigation canals were also invented in Mesopotamia, because southern Mesopotamia was dry and there was not enough rain for crops. So, people dug trenches to make water flow to irrigate their crops.

In ancient Babylon King Nebuchadnezzar built for his wife, beautiful gardens (the Hanging Gardens of Babylon), to enjoy. These gardens are believed to have been about 400 feet wide, 400 feet long to over 80 feet high. So, some historians believe that the gardens were built on a series of platforms that all together were 320 feet high. There were paths and steps, fountains and beautiful flowers, built to make a homesick queen feel welcomed and loved.

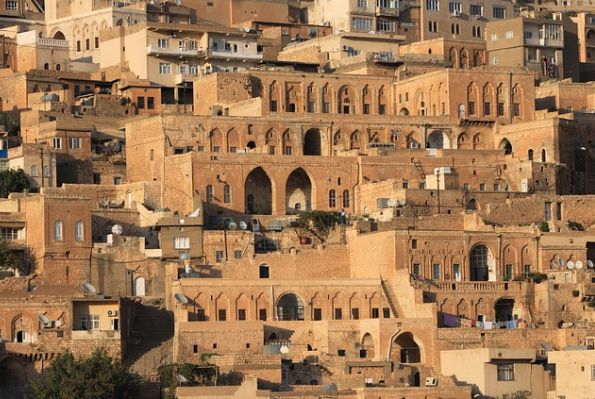

The Ziggurats

The Ziggurats were huge temples built by the Sumerians to honor their gods. They were huge temples with steps leading to the top where priests placed offerings of food and other goods.

Other inventions

Sailing ships, board games and chariots were also invented in Mesopotamia.

These inventions made it possible for people to communicate and move around better. They helped create more efficient ways of watering plants to grow more food. All of these inventions helped create better inventions for the future.

Most representative sculptures of Mesopotamian Art

• Below are some of the famous Mesopotamian statues and reliefs of the Neolithic art produced. As well as from Sumerian, Babylonian, Assyrian and Akkadian cultures. (All dates are approximate, B.C.).

• Neolithic female clay statuette from Samarra (6000): Louvre Museum, Paris.

• Uruk Warka period vase (3200): alabaster with carved reliefs, Iraq Museum, Baghdad.

• Silver statuette of a kneeling bull (3000) Proto-Elamite period, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

• Limestone statuette from a Proto-Elamite period.

• Lioness (2900): Brooklyn Museum, New York.

• Sumerian plaster/limestone votive statuettes (2600) Iraq Museum, Baghdad.

• Limestone stele of the Sumerian period, early dynastic III vultures (2600-2350): Louvre Museum, Paris.

• Copper relief of Imdugud between two deer (2500) British Museum, London.

• Spur in a thicket (c.2500), sculpture of gold, silver, copper, lapis lazuli and red limestone: excavated from the Great Pit of Death, now in the British Museum.

• Limestone/Lapis Lazuli Mosaic of Ur standard, British Museum (2500).