Sculpture during Christianity – History, Concept and Works

Contents

What is Sculpture in Christianity?

Sculpture in Christianity represents religious objects, being a medium of art that represents religious objects by means of stone, clay, wood or bronze. Roman architecture and sculpture became known throughout the civilized world, from Britain and France in the west, and India in the east. But just when Roman power was at its height an event happened that, in time, brought about a complete change in the way countless people lived and thought. Jesus Christ was born in Palestine and was crucified 30 years later. After his death his disciples traveled throughout the Roman Empire carrying their beliefs with them, and before long, small groups of Christians were found everywhere, along with early Christian art that illustrated their beliefs.

For nearly three centuries the Romans tried to suppress the new faith and the various types of Christian art that inspired it. But in the last in 313, Emperor Constantine decreed the Edict of Milan, in which Christians could worship God in their own way. Amazingly, less than 70 years later, Emperor Theodosius I declared that Christianity was the only authorized religion of the Empire.

How did Christian Sculpture develop?

Christian Sculpture in Churches

While Christianity was illegal, most of all fine art was funereal, particularly tomb sculpture, with reliefs on sarcophagi. After the Roman Empire became Christian, churches were needed everywhere. Thus, pagan temples were simply shrines built to house the statue of the god or goddess.

However, Christian churches had to be large enough to house a congregation of the faithful. Therefore, the first churches of the Roman Empire were built in imitation of the Roman basilicas, which were long aisles used as a marketplace or set of halls and courts. At first the new churches had no decorative art, especially no sculpture. The pagans had made sacrifices before the statues of their gods and worshipped them, so the early Christians thought that a statue was a pagan object. But although all agreed that they rejected statues, some did not feel so strongly about this conviction.

Toward the end of the sixth century Pope Gregory in Rome pointed out that since many Christians could neither read nor write, he felt that wall paintings on the walls of churches would help them remember what they had been taught about Christ and the Christian religion. Since about 400 years ago, when St. Jerome wrote a Latin version of the Bible (the Vulgate edition), priests had access to a standardized text, that facilitated the appearance of a wide range of biblical art illustrating stories from the Old and New Testaments.

In the beginning, images depicting God and Jesus were not allowed. Christians used symbols and signs to represent the Christ. One was the monogram we call the chi-rho, which is composed of the first two letters of the Greek word for Christ. Another was a fish, because the Greek word for fish is made up of the first letters of the phrase “Jesus Christ, son of God, Savior.” A hand protruding a cloud symbolizes God the father, with a dove, the Holy Spirit, a vineyard, the church, a mythical bird called Phoenix, the resurrection, and a peacock, the soul.

Sometimes the symbols that the Romans had used suggested honor and greatness, which was later used in Christian religious art as well. Thus, the Romans, for example, sometimes placed a halo behind the heads of emperors in paintings and statues. Christians put such halos behind the heads of holy personages, the Holy Family and saints to suggest holiness.

In 330, Emperor Constantine made the city of Byzantium, which was located at the southeastern tip of Europe, ending where Europe and Asia meet, as a second capital of the vast Roman Empire, and renamed it Constantinople. Likewise, a hundred years later, the Roman Empire had two emperors, one ruling the western or Latin-speaking half of Rome and the other ruling the eastern or Greek-speaking half of Constantinople. But as the eastern half flourished and grew richer, the other western half declined under attacks by Goths, Vandals and other barbarian tribes. Then in 455, Rome fell and was sacked and there was no longer a Roman emperor to rule in the west.

Byzantine Art

During the centuries that followed, Constantinople became the center of a great empire called the Byzantine Empire. The emperors in Constantinople became very rich and powerful indeed. Everywhere in the Byzantine Christian empire churches were built and Christian Byzantine art appeared, although executed in an oriental style. Thus instead of the walls being painted they were covered with mosaics, pictures of thousands of small pieces of colored glass and gold, magnificent and brilliant were made. Generally, however, while the works were dignified and majestic, the figures depicted in Byzantine mosaic art tended to be rather stiff. Thus, many artists depicted Christ, using symbols. At first a young man, much more like the Greek god Apollo than the figure we know today, because early Byzantine was an art carried in the traditions of ancient Greece.

The Crucifixion and Figurative Sculpture

In the beginning Christ was never actually shown on the Cross. To illustrate the crucifixion, artists place a lamb where the two arms of the Cross meet. Then, in the 6th century, the Council of Constantinople decreed that in depictions of the crucifixion, Christ must be shown in human form. Thus, later carved crucifixes, showed Jesus generally dressed in a long robe, with a crown on his head and with both feet together, as if he were standing erect with his arms outstretched in front of the Cross. We can see an example of such a crucifixion in an ancient relief that has survived at Langford in Oxfordshire. Unfortunately, the author is absent.

The Use of Images in Christian Art

The popes in Rome and the Byzantine emperors in Constantinople were often on very bad terms. So, they quarreled over many details of Christian belief and ceremonial and sometimes came to be really at war. So, one of the things they disagreed about was the question of images. Constantinople was in close contact with the peoples of the east, some of whom were not Christian, and their way of thinking about art, religion and life had influenced the people of the Byzantine empire in many ways. Thus, the Jews, for example, had always been opposed to images, and Jewish law forbade the use of them in Jewish art. Then in the 6th century Muhammad who was born in Mecca in Arabia and before that his followers in Syria, Palestine and Egypt, and the people of these and other countries became followers of Islam. Islamic art also prohibited artists from depicting human figures in paintings and sculpture and focused instead on non-objective art.

The early Christian aversion to images revived in the early Byzantine Empire in the 8th century with Emperor Leo III who issued orders that all sculpture and all paintings featuring figures were to be removed from Christian churches and that plaster was to be spread over mosaics. For more than a century this rule was in force in the Byzantine Empire, and ‘iconoclasts’ (image processors) broke many carvings and destroyed many paintings. Eventually the iconoclasts fell from power and the ban against the use of images was lifted, so mosaics and reliefs reappeared.

Early Christian Sculpture

Medieval Christian art in the West developed on the continent at the court of King Charlemagne during the period c.750-900 and at the court of Emperors Otto I, II, III during the years c.900-1050. In Ireland, they emerged during the 7th century and continued until the end of the 12th century.

Following the Byzantine tradition, Carolingian art at the court of King Charlemagne revived the art of ivory carving, typically illustrated in illuminated manuscript panels on both the front and back covers of the Lorsch Gospels, with the triumph of Christ and the Virgin, as well as crozier heads and other small items.

In addition, skilled goldsmiths produced a range of carved fastenings and metal reliefs that became an important element in the production of illuminated manuscripts in Aachen and elsewhere. Examples include the cover of the Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram (870), the cover of the Lindau Gospels (c.880), and the Arnulf dome (c.890), all in relief with its figures in embossed gold.

Another singular example of the skill of Carolingian goldsmiths is the Altar of Gold (824-859), now in the Basilica of Sant’ambrogio in Milan. Another masterpiece is the Lothair Crystal (c.855-69, British Museum). also, there is a series of some 20 pieces of rock crystal engravings, made in West Germany, depicting scenes from the biblical story of Susanna.

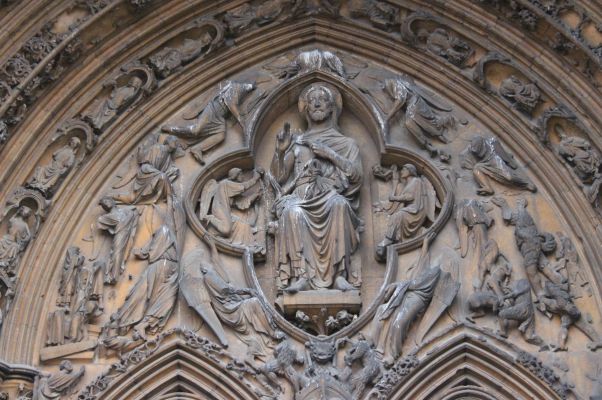

The sculpture of the great renaissance is reflected in the Christian church in Rome, when it regained confidence during the tenth century and began a program of church building in the style known as Romanesque, and which created a huge demand for this Christian Romanesque sculpture of reliefs largely over doorways and column statues.

What are the types of sculptures of Christianity?

Religious sculptures, of Christianity were works whose realization was made thinking in the representation of the religious theme, of the Christ, capturing actions performed by the deity of Jesus Christ, or by the saints, in the representation of these. Being that in most cases, they were used for religious worship, believing that they were the deities themselves and that through them you can reach the deity to intercede through supplications.

The primitive Christian artists mainly painted their sculptures in the catacombs, therefore, their artistic manifestations had a public dimension and a glorious and triumphant theme after the acceptance and formalization of the faith by the Empire.

The Prototypes

The identifiable Christian art of the second century consists of paintings on the walls and ceilings of the Roman catacombs (subway tombs). These continued to be decorated in a superficial style derived from Roman Impressionism until the 4th century. They provide an important record of some aspects of the development of Christian subject matter. Early Christian iconography tends to be symbolic. That is, a simple representation of a fish was sufficient to allude to Christ. Thus the bread and wine invoke the Eucharist. Therefore, during the third and fourth centuries, in catacomb paintings and other manifestations, Christians began to adapt known pagan prototypes to new meanings, for example the figure of the representation of Christ. Therefore, more often they show him as the good shepherd taken directly from a classical prototype. He was sometimes represented under the figure of familiar gods or heroes, such as Apollo and Orpheus. Only later, when religion had achieved some measure of earthly power, did he take on more exalted attributes.

The stories tend at first to be typological, suggesting parallels between the Old and New Testaments. The first scenes of Christ’s life to be depicted were the miracles. The passion, especially the crucifixion, was generally avoided until the religion was well established.

The Relief

These sculptures were made to recreate, for example, Christ’s entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday. Thus, the scenes are divided, in the classical manner, by columns. The technique is based on modeling and plays with the chiaroscuro effect provided by the trephine. Most of the Paleochristian sculpture also had a funerary character.

In this sense, the sculptural production will develop fundamentally in the decoration of sarcophagi, in which the Roman influence is clearly visible, combining Christian themes with those of pagan origin. Thus, Christian sarcophagi are derived from Roman sarcophagi and their decoration evolved from simple decoration with strigils, that is, with hollow, undulating moldings, to more complex friezes enclosing scenes between arcaded columns. Likewise, the carvings were influenced by the Jewish tradition against the representation of the divinity, very frequent and reduced to a few examples of the good shepherd.

The representation of the cycle of the life of Christ and some cycles of the Old Testament, representations of the saints, of Mary Most Holy, images of the Bible, the death of Jesus and the resurrected Jesus, the crucifixion and trial of Jesus, among others.

The places where these works were most exposed were in the Lutheran altars, in the traditional Catholic temples there was an abundance of all kinds of pictorial and sculptural representations, in places such as the main altar, side chapels, in the pulpit or the baptismal font, being also represented in the coffered ceilings and stained glass windows.

Depending on the historical period, the walls were covered with frescoes, canvases or altarpieces, and there were all kinds of architectural elements that served to support the sculptures, even in some areas not very visible to the faithful were decorated with works of Sacred Art.

Paleochristian Sculpture

The theme in this period was the representation of the Good Shepherd, also appearing figures such as the praying person with a variety of animals (doves, deer, peacocks or fish) that symbolized Christ, the soul, among others. There also appear themes of bucolic character, the chrismon, Christ’s monogram formed and linked by the initials of his name in Greek, from which also hang the first and the last letter – alpha and omega – of the Greek alphabet to define Jesus Christ as the beginning and end of all things. Likewise, the contents vary with the liberation of the Christian cult, becoming more common the themes of the beginning of the fourth century, from the Old and New Testament. Therefore, the sculptural production was carried out in the decoration of sarcophagi, with a clear Roman influence, initially combining Christian themes with those of pagan origin. Thus, the paleochristian sarcophagi, take the ideas of the Roman sarcophagi and in their decoration is present the evolution that goes from the simple ornamentation with strigiles, with hollow and wavy moldings to complex friezes of scenes between arcaded columns.

On the other hand, there are the carvings, which are influenced by the Jewish tradition against the representation of divinity, with a few examples of the Good Shepherd.

On the other hand, in Spain during the Middle Ages appeared the sculpture of the High Cross (c.750-1150 CE). It consists of monuments of different sizes, all of them based on the standard design of the Celtic Cross. These sculptures were decorated with abstract patterns or with narrative scenes from the Bible (rarely both), thus constituting the important body of free-standing sculpture produced between the fall of Rome (c.450) and the beginning of the Italian Renaissance (c.1400).

What is the legacy of Christian sculpture?

Christian sculpture was strongly influenced by Roman sculpture, which in turn was influenced by ancient Greece, and was characterized by being very realistic, being as faithful to life as possible. Therefore, the legacy of Christian sculpture, is embodied in the great cathedrals and basilicas in whose spaces was recorded in most of the temples and buildings, important reliefs, marble panels with deeply carved backgrounds so that the figures stand out in almost three dimensions. Likewise, this series of panels together told stories and depicted scenes of Christianity. Similarly, Roman-style reliefs were very influential throughout the history of Christianity, embodied in the reliefs with scenes from the Bible that decorate many of the most important and influential cathedrals in the world. Likewise, the figure of the Christ has a strong Roman and Greek influence, since it was they who studied the ideal proportions of the human body based on the golden ratio, a geometric formula. This ratio became the basis for the ideal standard of beauty, used in the sculpture of the Christ, the Virgin Mary, the saints and apostles, which is still used today.

Anyway, the theological and anthropological was always finely woven, producing cultural figures of which each has its beauty and being partly incomparable. Thus, first of all, it is required to consider that there are two factors that determine the sculpture of Christianity, one is the integration of the Eastern and Western church in its cult statues, (until the reaction of the reformation) and the other focus is on iconography. Therefore, there is also no difference between the theologies susceptible to the mystery of God made man, since in the west the emphasis is on the concepts of incarnation and resurrection, this one insists on illumination and transfiguration. It also contemplates, and is very important, happiness. However, in the West there is a desire to touch and develop an impressive cult of relics.

In this sense, in the traditional Catholic temples there is a great diversity of sculptural works, both in the main altar, as in the many chapels and side spaces, such is the case of the pulpit, the baptismal font, also in the coffered ceiling and stained glass windows. Likewise, the sculpture (historiated capitals, tympanums, gargoyles), are found even in areas not visible to the faithful, and even the floor is covered with tombstones. Likewise, the decoration of Orthodox churches is even more sophisticated (iconostasis, mosaics, clothing and religious goldsmithery). One of the emblematic cathedrals of Christian sculpture is the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris, one of the great representatives of Christian art used as an evangelizing tool. The windows are perfectly constructed and it is an architectural work of great beauty. Highlighting the gargoyles on the roofs, which are very characteristic of this cathedral.

Main representatives of Sculpture in Christianity

Michelangelo, with his impressive sculpture of the Pietà, a beautiful figure representing Christ dead and helped by his mother, the beautiful and sad Virgin Mary. The whole gives off a wave of solemnity and sadness, which have made it one of the most valued and visited sculptures of all time. In 1972, it was seriously damaged by hammering, so it had to be restored and protected with strong security measures. Likewise, the beautiful sculpture of Moses, in which the great genius of this Italian sculptor can be appreciated. A figure with latent strength and careful realism, so when admiring his sculptures, he is considered one of the best sculptors of all time.

Similarly, another of his representative works was the crucifix of Santo Spirito, which is a sculptural work of Michelangelo’s youth, located in the sacristy of the Basilica of Santo Spirito in Florence.

The Angel, candelabra holder, also a marble sculpture, made by Michelangelo in 1494 for the Ark of St. Dominic in the Basilica of St. Dominic in Bologna.

Niccolò dell’Arca (c. 1435 – Bologna, 1494), was also an Italian sculptor active in Bologna, northern Italy in the 15th century. Some of his works were the angel of the candelabrum, the weeping of the dead Christ, the ark of St. Dominic, from the Basilica of St. Dominic in Bologna. He also received some commissions, among them the coffered windows on the east side of the Basilica of San Petronio.