Most important aspects of Romanesque sculpture

Contents

Definition of Romanesque Sculpture

The 18th century Arts movement known as Neoclassicism represents a reaction against the late Baroque phase and a reflection of the growing scientific interest in classical antiquity. Archaeological investigations of the classical Mediterranean world compelled testimony to the order and serenity of classical art, providing a backdrop of adjustment to the enlightenment and the age of reason.

Academic theorists, especially those in France and Italy during the seventeenth century, argued that the expression, costume, data, and configuration of a work should match the subject matter as closely as possible. Thus, in the 18th century, in particular, the neoclassicals inherited this theory of “decorum,” but instead of giving preference to a universal ideal, they implemented the restricted form. Subdividing all action and expression into classical repose, idealizing faces and bodies into classical heroes and transforming all costume into tight clothing to avoid reference to ephemeral time.

A series of 18th and early 19th century monuments to generals and admirals of the Napoleonic Wars in St. Paul’s Cathedral and Westminster Abbey demonstrate this important resulting dilemma, of whether a hero or famous person should be portrayed in classical or contemporary costume.

Therefore, many sculptors varied between showing figures in uniform and completely nude. Likewise, the concept of the modern hero in ancient dress belongs to the tradition of academic theory, exemplified by the English painter Sir Joshua Reynolds in one of his speeches at the Royal Academy, stating the desire to transmit to posterity the form of modern dress. Even the hero of life could be idealized totally nude, as in two standing figures of the colossal Napoleon (1808 – 11), by the Italian sculptor Antonio Canova. One of the most famous sculptures in neoclassical style is “Paolina Borghese as Venus Victrix” also by Canova (1805-07; Borghese Gallery, Rome). She is shown nude, lightly draped and sensually reclining on a sofa, a lovely contemporary portrait and an idealized ancient Venus.

How did Romanesque sculpture develop?

The age of Neoclassicism and Romanticism both span roughly the late 18th and 19th centuries. These movements flourished throughout Western Europe (especially in the North), the United States, and to a lesser extent Eastern Europe.

Two main forces contributed to the rise of Neoclassicism, the reaction against the extravagance of Baroque and Rococo and the renewed interest in antiquity due to the excavation of several important classical sites (including Pompeii and Athens). Thus, these forces compelled artists from all over Europe to collaborate in a classical revival.

On the other hand, many artists grew impatient with the constraints of classicism and baroque. Rather than starting with a preconceived aesthetic structure (the stability of classicism) or the dynamism of the baroque, these artists were guided by emotion, in an approach known as romanticism. Thus, the aesthetic structure of Romantic work was not predetermined, but arises naturally as the artist strives to capture particular feelings. Thus, Romantic art is also distinctive for a number of typical themes, such as, nature, historical nostalgia and social struggle.

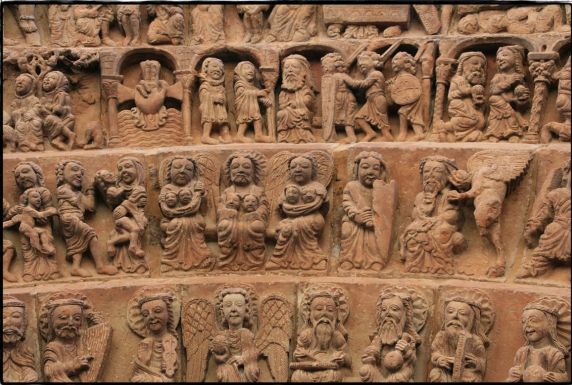

In this sense, Romanesque sculpture featured artists of a great empire of changing public tastes for centuries, in which, above all, was its remarkably great variety and eclectic mix. Thus these sculptures blend the idealized perfection of earlier classical Greek sculpture with a greater aspiration for realism, also absorbing the artistic preferences and styles of the East to create images in stone and bronze that rank among the finest works of antiquity. Apart from their unique contribution, the Romanesque sculptors have also, their popular copies of earlier Greek masterpieces, preserved in priceless works for posterity that would otherwise have been completely lost to the art of the world.

Copied Sculptures

Taking Greek sculpture as their principles, the Romans worked in stone, precious metals, glass and terracotta, however, their favorite materials were bronze and marble mainly for the achievement of better workmanship. However, since metal was always in great demand for reuse, most examples of Romanesque sculpture are in marble. Similarly, the Roman taste for Greek and Hellenistic sculpture meant that once the supply of original pieces had been exhausted, sculptors had to make copies and these could be of varying quality depending on the skill of the sculptor. In fact, there was a school specifically for copying Greek originals in Athens and Rome, headed by Pasiteles along with Archesilaos, Evander, Glykon and Apollonios. Likewise, an example of the work of the school of this first century B.C. is the marble statue of Orestes and Electra, now in the Archaeological Museum of Naples. In addition, Romanesque sculptors also produced miniaturized copies of Greek originals, often in bronze, which were purchased by art lovers to display in their home cabinets.

Impressionist Sculpture

In this sense, Romanesque sculpture, however, began to seek new avenues of artistic expression, moving away from its Etruscan and Greek roots, in the middle of the 1st century BC. Hence, Roman artists tried to capture and create optical effects of light and shadow for greater realism. This fact later marked the step towards impressionism with tricks of light and abstract forms. Similarly, Romanesque sculpture also became more monumental with larger statues of the lives of emperors, gods and heroes such as the huge bronze statues of Marcus Aurelius on horseback or the largest statue of Constantine I (only the head, hand and some limbs survived). Both now reside in the Capitoline Museums in Rome. Likewise, at the end of the Empire, the sculptures tend towards lack of proportion, with the heads especially were enlarged, and the figures are presented more flat and frontal, showing the influence of oriental art.

It is also important to distinguish two distinct ‘markets’ for Romanesque sculpture, the first being the taste of the ruling aristocratic class for more classical and idealistic sculpture. While the second, ‘middle class’ market was more provincial, so they seem to have preferred more naturalistic and emotional sculpture and funerary portraiture. Although it is believed that the limitations of the artists in the larger urban centers may also have had something to do with the differences in styles. An interesting comparison of the two approaches can be found in Trajan’s column in Rome and a trophy in Adamklissi commemorates the Dacian campaigns.

Funerary Sculpture

Funerary busts and stelae (tombstones) were one of the most common forms of sculpture in the Romanesque world. These sculptures can portray the deceased alone, with their companion, children and even slaves. Thus, the figures usually wear a toga and the women may hold the pudicitia posture with their hand on their chin in remorse. Altar tombs were also common and these could bear relief scenes of the life or deeds of the deceased and the richer ones could portray different generations of family members.

What is the legacy of Romanesque sculpture?

Like the Greeks, the Romans represented their gods in statues. Therefore, when Roman emperors began to claim divinity they also turned to the subject of colossal and often idealized statues, depicting these personages, with one arm raised to the masses and striking a pose conveniently authorized by Augustus of Prima Porta.

Similarly, the statues could also be used for decorative purposes in the home or garden and could be miniaturized, especially in precious metals such as silver. One type of such statues peculiar to the Romans was the Lares Familiar. These were made in bronze and represented the spirits protecting the home. These sculptures were typically displayed in pairs in a niche within the house and are youthful figures with raised arms and long hair usually wearing a tunic and sandals.

In relation to Romanesque sculpture on buildings, the same could be merely decorative or have a more political purpose, for example, triumphal arches (often celebrating military victories). Similarly, architectural sculpture captured acts of campaigning with key details that reinforced the message that the emperor was a civilizing and victorious agent throughout the known world. A typical example is the Arch of Constantine in Rome (c. 315 CE) which also shows the defeated and enslaved barbarians sending the message of Rome’s superiority. Similarly, on columns such as Trajan’s column (c. 113 CE), sculpture could show the emperor as a leader of good, meticulously prepared, as an innovative and inspiring military innovator suitable for his troops. Such depiction of real people and specific historical personages in architectural sculpture is in stark contrast to Greek sculpture where great military victories were usually presented in metaphor with figures from Greek mythology such as the Amazons and the Centaurs on the Parthenon.

What are the representatives of Romanesque Sculpture?

Much of the Sculpture of the Romanesque Period is anonymous. The works are known rather than their authors. For example, the 3.52 meter gilded bronze equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius is one of the most imposing bronze statues surviving from antiquity. It was probably erected between 176-180 CE at an unknown location in Rome. The statue commemorates the emperor’s victories over the Germanic tribes in 176 CE and his death in 180 CE. The remarkable survival of the statue has been credited to Emperor Regulus Constantinus. Much restoration work was needed in the late 1980s as the statue had been slowly eroded in the open air, however, it now takes a place in a hall built in the Capitoline Museum in Rome.

On the other hand, the Master of Cabestany was another sculptor of the Romanesque period, active in the 12th century, who exerted an enormous influence in his time. Likewise, the sculptor Arnau Cadell or Gatell was a Spanish sculptor of the twelfth and thirteenth century, author of the capitals of the cloisters of the monastery of Sant Cugat in 1190 and the cathedral of Gerona.

Likewise, Anselmo da Campione, made sculptural works in the cathedral of Modena which is one of the most important Romanesque style places in Europe and at the same time a World Heritage Site.