Gothic Sculpture, interest in nature

Contents

What is Gothic Sculpture?

Gothic is only a technical term for the type of building in which the arches are pointed. Architecturally the possible nuances of the transition from Romanesque to Gothic and even from Byzantine to Gothic art are infinite. However, Venice is full of Gothic buildings by definition, but it is Byzantine in spirit. The buttressed arches of Monreale in Sicily are more closely related to Byzantine than the round arches of Durham. Likewise, reflecting the growing stability of this time, as well as the growing power and ambition of the Christian church, cathedrals were built based on this Gothic movement designed as a small symbol of God’s universe. Each element of the building’s design conveys a theological message of the awe of God’s glory. The ordered nature of the structure reflects the clarity and rationality of God’s universe, while the sculptures (reliefs and column statues), stained glass windows and murals illustrated the scriptural messages of the Bible. The craftsmen involved included Europe’s greatest sculptors, yet they remained largely anonymous.

How did Gothic Sculpture develop?

The permanent significance of Gothic art is that it is applicable not only to a cathedral, but also to statues and reliefs. Instead of limiting itself to humanity, Gothic has developed in the direction of complexity and beauty and joyfully blended the grotesque with the elegant. It is this mixture that gives it its true value and therefore, it is not limited to a statue or a painting. Thus Gothic art in its separate aspects does not represent enough of the value that the integrated work has already in its final stage as it has all the complexity of life itself. To see the Gothic in its impressive beauty, it is enough to contemplate the great cathedrals, especially the cathedrals of northern France. Thus, cathedrals are among the most extraordinary creations of man. If one sees them from afar, they proudly recreate the city around them and break upwards into spires and pinnacles. If one examines them more closely, one observes the infinite and restless sculptural detail and frets of texture. But if you enter them, you will find a complex architectural system whose soaring pillars and ribbed vaults, to the naked eye, are so efficiently crafted that the walls are barely noticeable and the effect is more like a formalized forest than an enclosed room.

What is most striking about Gothic art is not its form or function but its ability to provide an ideal environment for a certain kind of fine art. The Gothic spirit is not only vertical. Its essence lies in its ability to suggest not the ultimate perfection of classical reason, like a Greek temple, but a dynamic search for the unattainable. The secondary arts of sculpture and stained glass that it so readily fostered seem to grow organically out of it rather than being imposed. Like a living plant, a Gothic building can enrich itself from its own roots, shed leaves, tendrils and flowers without losing its central unity. Likewise, the nervous energy on which the whole Gothic structure is based is communicated to all parts of the building but particularly to those parts which, while they cannot be embedded in the design of the whole, can at least be considered as belonging to the separate category of sculpture.

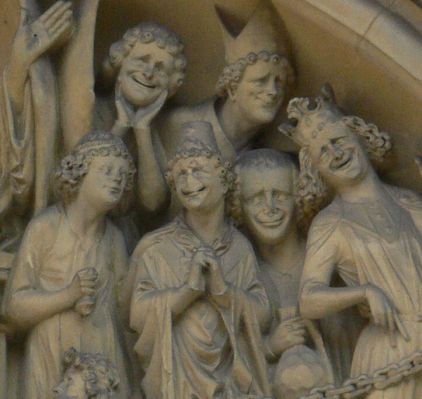

In a purely physical sense, a great Gothic sculpture can be extracted from its architectural context and still claim admiration not only for its vitality, its fantasy, and its grace, but also for its inherent and independent significance. Nevertheless, a number of carved statues of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries could be taken out of their niches and placed alongside the best of the statues of Italian Renaissance sculpture without suffering from the comparison. But because the sculptors were largely anonymous and because their creations were almost an invariable contribution to a conception that was greater than themselves (and because few appear in the best art museums), it is difficult to think of even the best of the Gothic sculptures as a series of masterpieces, because they are masterpieces in themselves, in the certainty of their craftsmanship and in the grace and nobility of their conception.

The anonymity of Gothic art in general and Gothic sculpture in particular offers an obstacle to the art historian of which he himself is scarcely aware. The three doors on the west side of Rheims Cathedral alone contain 33 life-size figures and 200 smaller figures, each the product of a creative mind with passion and a fully developed tradition of craftsmanship. And when one remembers that this impressive collection of medieval sculpture is contained within a comparatively small area of one among a hundred similar buildings, one is struck by the extraordinary fecundity of the 13th and 14th centuries in northwestern Europe. Likewise, much has been written of Gothic carving since Ruskin’s famous chapter on ‘The Nature of Gothic’ in The Stones of Venice. Inevitably, however, the art historian, faced with a mass of anonymous Gothic sculptural works of art, tends to regard them as products of a period, rather than a collection of exceptional individuals. In spite of himself, he takes refuge in generalizations.

In this sense, the Gothic period was dominated by cathedrals in the cities, which were characterized not only by their lofty silhouette, but also by their political, economic and religious influence. The Cathedral is the monument that defines what we call Gothic architecture. This term, given prominence by the Romantics, was applied to the new style of religious art that originated in the Ile de France and flourished first in northern France, spreading to neighboring lands during the second half of the twelfth century and the following two centuries.

The sculpture of the period of Gothic expansion was conceived primarily for the embellishment of cathedrals, with Christian religious sculpture of a different era and an entirely different function. Thus, since Gothic sculpture, the Cathedral and its decoration was the symbol of a communal organization, of a secular spirit that had taken precedence over monasticism and feudalism. Therefore, as trends of the neo-Gothic style in architecture, cathedrals became very popular throughout Europe from the end of the 18th century, taking into account the formal, symbolic and technical for the valuation of both sculpture and architecture.

The Column Statue in Gothic Sculpture

Major Gothic sculpture was born and evolved to the rhythm of the cathedrals, of which it was the external adornment, in the same way as the precious decorations of the great Gothic sanctuaries made by goldsmiths. Thus, sculpture invaded the facades of the Cathedral, and is intimately conjugated to its severe architecture helping in the pattern of its division into floors. Thus, the towers that were erected over the side naves closed the central part of the facade and rose solidly supported by the powerful buttresses. The latter went unnoticed at ground level because of the fullness and depth of the extended jambs of the portals, which the monumental sculpture helped to lighten. The whole of the tympanum, the arch moldings, the mullion, the statues and pedestals make up the Gothic portal. Likewise, its iconography would have considerably expanded the religious content of Romanesque facades by closely associating the moldings of the arches and spurs with the tympanum. Among the themes carved on them, in addition to the apocalypse and the Last Judgment, are scenes from the Old Testament corresponding typologically to those of the New Testament. Each event of the old covenant period refers to an episode of the new covenant. Thus Jonah’s sojourn in the whale prefigures Christ in the tomb, and Abraham sacrificing Isaac evokes the sacrifice of the Cross. Matthew, the church fathers and some medieval theologians have established these typological comparisons very clearly. A great number of portals offer the faithful the example of the lives of the Saints. The Virgin occupies a privileged place. Thus, according to the classification proposed by Emile Male, the following set corresponds to the different mirrors of Gothic Christianity: nature and morals and historical science.

Monumental sculpture also invaded the upper parts of the Gothic façade: gables, rose windows, galleries, among others. Outside the building, flying buttresses and spurs form aerial locations, almost like tabernacles, where statues were housed. Inside, architectural sculpture can cover the mural surfaces, as in the interior facade of the Cathedral of Reims, but this is unusual, since they are sculpted pillars like the one in the Cathedral of Strasbourg.

On the other hand, statues appeared very early on the pillars of the choir and nave as in the Sainte Chapelle (1241-48) in Paris and Cologne Cathedral. On the other hand, carved capitals no longer had the iconographic role they had in the Romanesque period. The screen of the Cross closing the liturgical choir provides a new carved wall. However, the cathedral was also adorned with cult statues, altarpiece art, carved furniture and tombs, whose careful arrangement had become essential to the overall iconography.

What is the legacy of Gothic Sculpture?

Monumental sculptures assumed an increasingly prominent role during the High and Late Gothic periods and were placed in great numbers on the facades of cathedrals, often in their own niches. In the 14th century, Gothic sculpture became more refined and elegant and acquired a mannered delicacy in its elaborate and meticulous drapery. The elegant and somewhat artificial beauty of this style spread widely throughout Europe in both sculpture, painting and manuscript illumination in the 14th century and became known as the international Gothic style. An opposing trend at this time was that of intensified realism, as shown in the French tomb sculptures and in the vigorous and dramatic work of the Gothic sculptor, Claus Sluter. Likewise, Gothic sculpture was always linked to architecture, as it was mainly used to decorate the exteriors of cathedrals and other religious buildings. The first Gothic sculptures were stone figures of the saints and the holy family to decorate the doors or portals of cathedrals in France and elsewhere.

The sculptures above the royal portal of Chartres Cathedral (c. 1145-55) changed little from their Romanesque predecessors in their rigid, straight, simple, elongated and hieratic modes. But during the later twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the sculptures were more relaxed and natural in treatment, a trend that culminated in the sculptural decoration of Rheims Cathedral (c. 1240). These figures, retaining the dignity and monumentality of their predecessors, have individualized faces and figures, as well as being the complements of draperies and natural poses and gestures, showing a classical balance, suggesting an awareness of ancient Roman models on the part of their creators. Gothic Masonic principles are also evident in the natural forms of the plants, being evident of the realism, the embossing of the clusters of leaves that adorn the capitals of the columns.

Who are the main representatives of Gothic sculpture?

Undoubtedly there existed in medieval France, Germany and England, individual sculptors, each of whom is worthy of separate study such as Nicola Pisano (c.1206-1278), Giovanni Pisano (c.1250-1314), Arnolfo di Cambio (c.1240-1310), Giovanni di Balduccio (c.1290 – 1339), Andrea Pisano (1295-1348), Filippo Calendario (pre-1315-1355), Jacopo della Quercia (1374-1438) and Donatello (1386-1466), but since their work is shown without their names, it lacks the attention of art historians.