Ancient Greek Sculpture – Definition, History and Representatives

Contents

What is Ancient Greek Sculpture?

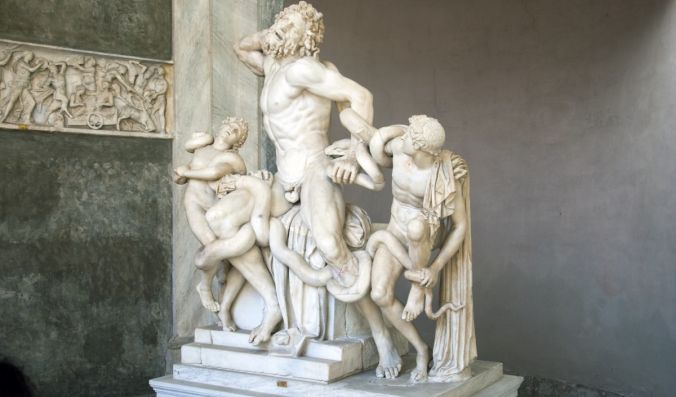

Ancient Greek Sculpture from 800 to 300 B.C. took early inspiration from the monumental art of Egypt and the Near East and over the centuries evolved into a uniquely Greek vision of the art form. Greek artists would reach a peak of artistic excellence that captured the human form in a way never before seen and which has been widely copied.

Likewise, these Greek sculptors were particularly concerned with proportion, balance and idealized perfection of the human body, and their figures in stone and bronze have become some of the most recognizable pieces of art produced by any civilization.

How did Ancient Greek Sculpture develop?

From the 8th century BC, archaic Greece saw an increase in the production of small solid figures in clay, ivory and bronze. Undoubtedly, wood was also a medium used but its susceptibility to erosion has meant that few specimens have survived. Similarly, bronze figures, human heads and, in particular, griffins were used as attachments to bronze vessels such as cauldrons. Likewise, in this style, human figures resemble contemporary designs, with geometric ceramics, elongated limbs and a triangular torso. Likewise, animal figures were also produced in large quantities, especially the horse, and many have been found in Greece at sites in the sanctuaries of Olympia and Delphi, indicating their common function as votive offerings.

In this regard, the oldest Greek stone sculptures (limestone) date from the 7th century BC and were found in Thera. In this period, freestanding bronze figures with their own base became the most common, also, more ambitious subjects such as warriors, charioteers and musicians were treated. Similarly, marble sculpture appeared in the early 6th century B.C. and the first monumental, life-size statues began to be produced. These had a commemorative function, offered in sanctuaries as a symbolic service to the gods or used as markers in tombs.

On the other hand, the first large stone figures (kouroi – young naked males and kore – female figures) were rigid as in monumental statues with arms straight at the sides, feet almost together and eyes staring blankly and without any facial expression. These rather static figures evolved though slowly as if they were coming to life, with more and more details in the hair and muscles. Thus, slowly, the arms are shown slightly deformed giving them muscular tension and one leg (usually the right) is placed a little more forward, giving a sense of dynamic movement to the statue.

Excellent examples of this style of figure are those of the kouroi of Argos, dedicated at Delphi (c. 580 B.C.). Then, around 480 B. C, the kouroi passed became increasingly realistic, the weight is carried on the left leg, the right hip is low, the buttocks and shoulders more relaxed, the head is not so stiff, and there is a hint of a smile. Similarly, the Kore, i.e. women followed a similar evolution, particularly in the sculpting of their clothes that were sculpted in an increasingly realistic and complex manner. Likewise, a more natural part of the figure was established, where the head was given greater proportion to the body, regardless of the actual size of the statue. Thus, by 500 B.C. Greek sculptors were finally breaking away from the rigid rules of archaic conceptual art and beginning to return to producing what was actually observed in real life.

Types of Ancient Greek Sculpture

Early Greek Sculpture was most often in bronze and porous limestone, but while bronze never seems to have gone out of fashion, the stone of choice would become marble. Likewise, it went from Naxos – close grained and sparkling, Paria (from Paros) – with a rougher and more translucent grain and Pentelic (near Athens) – more opaque and then turning to a soft honey color with age (due to its iron content). However, the stone was chosen for its work rather than its decoration, like most Greek sculpture, it was not polished but painted, often somewhat glossy for modern tastes.

Moreover, the marble was quarried using bow drills and wooden wedges soaked in water to break up the blocks. In general, the larger figures were not produced from a single piece of marble, but important additions such as the arms were sculpted separately and attached to the body with blocks. Similarly, with the use of iron tools, the sculptor would fuse the block from all directions (perhaps with the eye on a small scale model to proportions), first using a pointed tool to remove the most important pieces of marble. Next, a combination of a five-claw chisel, flat chisels of different sizes, and small hand drills were used to carve out the fine details.

The surface of the stone was then finished off with an abrasive powder (usually Naxos emery) but rarely polished. The statue is then connected to a plinth with a lead lamp sometimes placed on a single column (e.g., the Naxian sphinx at Delphi, c. 560 B.C.). Likewise, finishing touches were added to the statues with paint. Thus, skin, hair, eyebrows, lips and patterns on clothing were added in bright colors. Likewise, eyes were often inlaid using bone, glass or crystal. Finally, bronze additions could be added such as spears, swords, helmets, jewelry and diadems, and some statues even had a small bronze disk (meniscus) suspended above the head to prevent birds from disfiguring the figure.

The other preferred material in Greek sculpture was bronze. Unfortunately, this material was always in demand for reuse in later periods, while broken marble was not of much use to anyone, so marble sculptures were those that have best survived for posterity. Consequently, the number of examples of bronze sculpture (no more than twelve) that managed to survive is perhaps not indicative of the fact that bronze sculpture may have been produced in greater quantity than marble sculpture and demonstrates the quality of the few surviving bronzes, the excellence of which has been lost. Very often at archaeological sites one can see rows of bare stone plinths, mute witnesses to the loss of the art.

Early solid bronze sculptures gave way to larger pieces with a bronze core that was sometimes removed to leave a hollow figure. The most common production of bronze statues used the wax technique. This was accomplished by making a core nearly the size of the desired figure (or body part) which was then covered with wax and the details sculpted. Everything was then covered with clay fixed to the base at certain points by means of rods. The wax was then melted out and molten bronze was poured into the space once occupied by the wax. When set, the clay was removed and the surfaces finished by fine scraping, engraving and polishing. Sometimes additions of copper or silver were used for the lips, nipples and teeth; the eyes were made of marble inlaid into the sculpture.

What is the legacy of Ancient Greek Sculpture?

Greek sculpture broke with the artistic conventions that had prevailed for centuries in many civilizations, and instead of reproducing figures according to a prescribed formula, they were free to pursue the idealized form of the human body. Likewise, the hard, lifeless material was magically transformed into intangible qualities such as balance, humor and grace by creating some of the great masterpieces of universal art and inspiring and influencing the artists who would follow in Hellenistic and Roman times to produce more masterpieces such as the Venus de Milo. In addition, the perfection in the proportions of the human body achieved by Greek sculptors continues to inspire artists even today. The great Greek works are still consulted by 3D artists to create accurate virtual images and by athletes in sports and entertainment, who have compared athletic bodies with Greek sculptures to check the abnormal muscle development achieved through the use of banned substances such as steroids.

Main representatives of Ancient Greek Sculpture

The most famous of all Greek sculptors was Phidias, the artist who created the giant chryselephantine statues of Athena (c. 438 B.C.) and Zeus (c. 456 B.C.) that resided, respectively, in the Parthenon in Athens and the temple of Zeus at Olympia. The latter sculpture was considered one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. Another famous sculptor of this period was Polyclitus, who in addition to creating great sculptures such as the Doriphorus, also wrote a treatise, the Kanon, on sculpting techniques where he stressed the importance of correct proportion. Other important sculptors were Kresilas, who made the oft-copied portrait of Pericles (c. 425 B.C.). Also famous, Praxiteles, who sculpted Aphrodite (c. 340 B.C.) which was the first full female nude and Kallimachos, who is credited with creating the Corinthian capital and whose distinctive dancing figures were copied by many in Roman times.